Deep in the forests of Utah lives one of the largest and oldest living organisms on Earth—a clonal colony of quaking aspen trees known as Pando. To the casual observe just a forest. But what if this massive tree colony is actually part of something more? Something intelligent, reactive, and distributed? What if the key to Pando’s survival lies not in its roots—but in the fungi beneath them?

What Is Pando?

Pando is a single organism made up of over 40,000 genetically identical quaking aspens, all connected by a massive underground root system. It’s estimated to be thousands of years old and covers over 100 acres. Despite its size and longevity, Pando is struggling—and scientists are still trying to understand exactly why.

Is Pando in Danger?

While Pando has persisted for thousands of years, recent studies show that it may be in decline. The biggest threat? Overbrowsing by deer and elk, whose populations have exploded in the absence of natural predators. These animals feed on the young shoots that Pando sends up from its massive root system, effectively preventing regeneration.

In addition, climate stress from drought and warming temperatures is straining the older trees, while human infrastructure—like roads and fencing—has fragmented the colony and disrupted soil health.

A 2018 study led by ecologist Paul Rogers found that much of Pando is not successfully regenerating, especially in areas left unprotected. Although the root system remains genetically alive, the visible forest may continue to decline unless active restoration and protection efforts are made.

In this context, exploring Pando’s underground relationships isn’t just an academic exercise—it may be essential to understanding how to help it survive.

Enter the Fungi

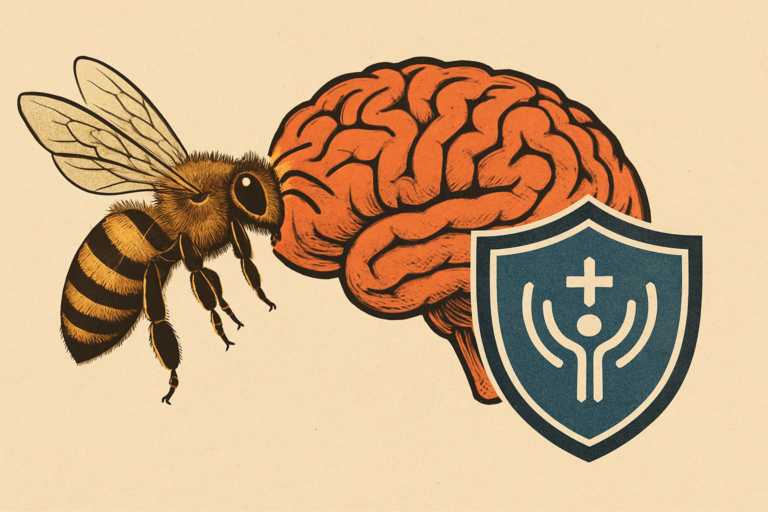

Aspens, like most trees, form mycorrhizal relationships—mutualistic connections with underground fungi that help exchange water, nutrients, and chemical signals. These fungal networks, often called the “wood wide web,” are known to interconnect trees, redistribute resources, and respond to environmental change. But their role in clonal superorganisms like Pando has never been deeply explored.

A Thought Experiment Takes Root

What if we treat the fungal network not just as a helpful sidekick—but as part of an extended intelligence? A Fungal-Class Distributed Reactive Intelligence (FDRI), as we’ve begun calling it, could act like a brainless, decentralized mind—sensing, responding, and adapting over long timescales. It wouldn’t think in the way we do, but it might react, remember, and adapt.

How Would We Test This?

To move from speculation to science, we’d need to ask bold, but testable questions:

- Are nutrients flowing between trees via fungi, not just roots?

- Does disrupting fungal networks reduce Pando’s resilience?

- Can fungal signals anticipate or respond to environmental stress?

- Do these networks exhibit something like memory?

Fortunately, there are tools—DNA sequencing, isotope tracing, microelectrodes—that can help us test these ideas.

Why It Matters

If Pando is more than just a giant tree—if it’s part of a symbiotic, intelligent system—it could change how we view ecosystems, intelligence, and even life itself. It blurs the lines between individual and colony, organism and environment, biology and behavior. And it reminds us that intelligence might not always come with a brain.

Final Thoughts

We still have much to learn about the hidden relationships that sustain life on Earth. But one thing is clear: the deeper we look into the soil, the more we discover just how interconnected—and possibly intelligent—nature really is.