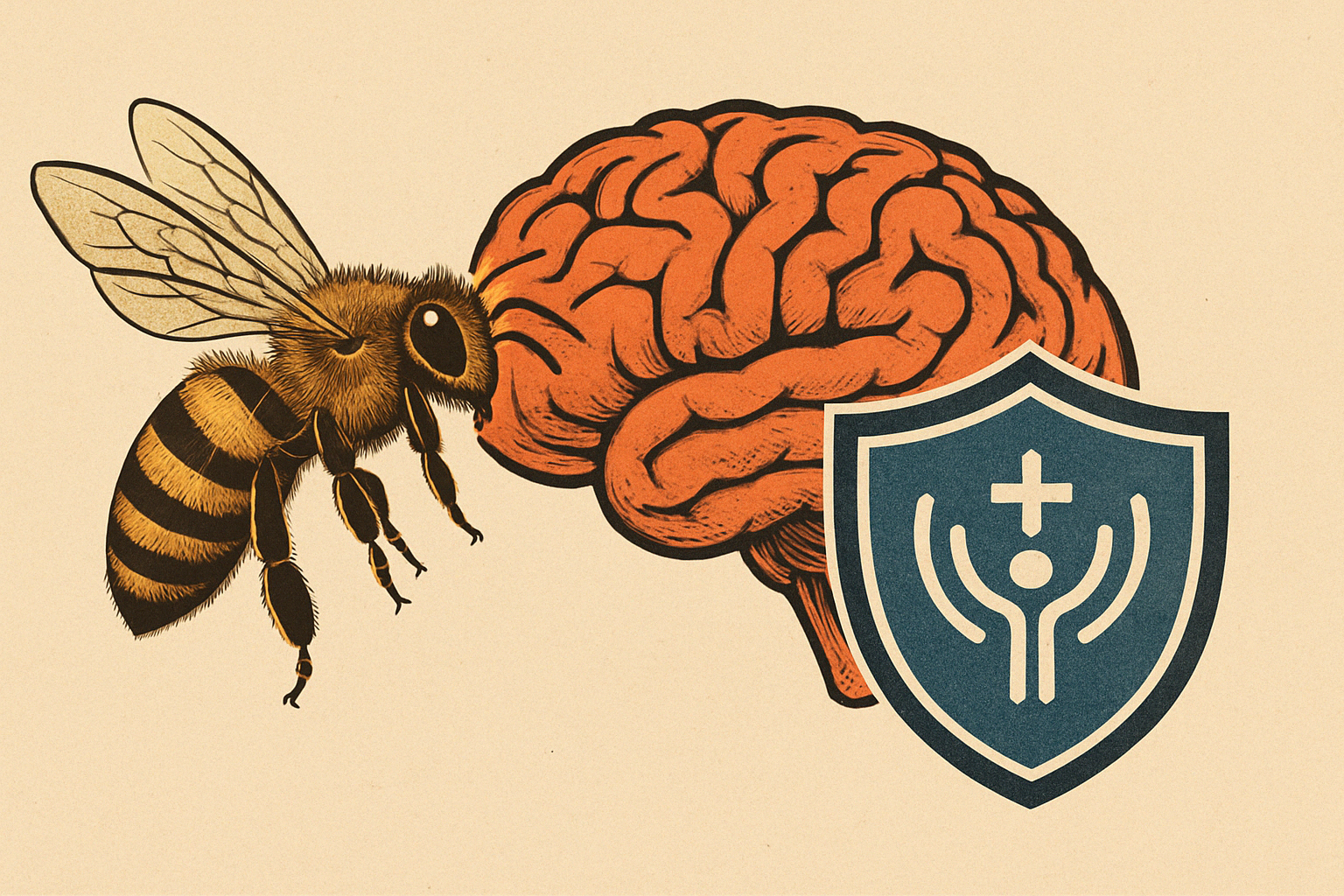

There was a time, years ago, when a strange idea quietly took root in my mind—one I never acted on, but never forgot either. I was thinking about my immune system, and how in multiple sclerosis, it’s not a lack of vigilance that causes harm—it’s an immune system turned inward. An overzealous guardian mistaking the self for a threat. What about bee venom and MS immunity? Could it help?

And I wondered: what if it needed a real threat? What if it just needed to be distracted?

The idea was this: get stung. On purpose. Give the immune system something external to deal with. Bee venom is known to be inflammatory in some ways, but paradoxically, it’s also been used in ancient medicine to calm chronic conditions. That duality caught my attention.

But I never did it.

Not because I thought the hypothesis was wrong, but because I couldn’t justify the cost—not to me, but to the bee. Honeybees die after they sting. They are keystone creatures in our ecological web. Sacrificing them for personal experimentation felt unethical, even desperate. And if I’ve learned anything from illness, it’s that desperation can’t be your compass.

Bee Venom and MS Immunity

Later, I discovered I wasn’t the only one to think this way. Bee venom therapy—called apitherapy—is a real thing. It’s been studied for MS and other autoimmune diseases. Compounds in venom like melittin and apamin have been shown to reduce neuroinflammation and modulate immune responses in controlled settings.

But these studies mostly use purified or synthetic venom, not live bee stings. And that matters.

Because the real insight—the one that still lingers with me—isn’t about bees. It’s about how modern life has stripped the immune system of its training grounds. We live in environments scrubbed clean, filled with plastic particles, synthetic fabrics, and low-grade immune irritants—but little that teaches our immune system what a real threat looks like. No parasites. No meaningful microbial diversity. No true predators.

So the immune system turns inward.

What Else Could Serve the Same Role?

There are therapies now that use controlled exposure to intestinal worms (helminthic therapy), or that introduce immunomodulating bacteria to help reset immune calibration. Some plant compounds mimic inflammatory triggers in more manageable ways.

I wonder how many chronic illnesses like mine are, in some way, diseases of modern sterility—not infections of too much, but absences of the right kind of something.

Where That Leaves Me

I still won’t hurt a bee to find out. But I’ll continue searching for that “sting that never comes”—a stimulus strong enough to remind my immune system that the war isn’t here, within me. It’s out there, in the world it no longer sees clearly.

Until then, I do what I can. I reduce the microplastics, I question the sterilized environments, and I listen to my body like it’s a partner in an uneasy truce. Sometimes I wonder what I could do if the right lab heard this voice. But even if they don’t—I’ll keep sharing it.

Because someone out there might be thinking the same strange thought. And maybe they’ll take it further.

Further Reading

References

(https:/